(a personal perspective on how OSU squandered public trust in managing their research forests – and what their leaders should do to restore it)

I’ve been a firsthand observer of OSU’s forest management practices for more than three decades as a neighbor and recreational user of their McDonald-Dunn Research Forests. In my 36 years of running, biking, and bushwhacking in the “Mac-Dunn”, I have explored nearly every section of these ecologically-diverse forests. I’ve formed a close connection with many special places – and have seen many of them destroyed by OSU’s clearcut logging. I’ve also participated in OSU’s forest planning processes, from meeting with the university president and deans of the College of Forestry (CoF), to attending meetings and providing input.

A history of broken trust: In the mid-90’s I joined a group of neighbors who were concerned about the College’s management of the newly-acquired Cameron Tract (located in the Soap Creek Valley near Corvallis). OSU planned to clearcut a large section of the forest to pay for the construction of their Valley Library and an endowed chair in the College of Forestry. We met with the OSU president and initiated a public meeting with the dean (George Brown) and his research forest staff. Roughly 70 neighbors showed up to share our concerns about such things as herbicides polluting our wells, erosion from the planned clearcuts, and safety risks of logging trucks on our narrow, curvy roads. The dean promised to hold a second meeting to provide answers to our many questions. Several weeks later, neighbors received letters from Dean Brown thanking us for our input – and notifying us that cutting would begin soon. There was NO mention of the meeting he’d promised nor answers to our concerns. This was my first lesson in how leaders of OSU’s College of Forestry deal with the public: they begrudgingly accept public input, but reject most of it; promises mean nothing.

When I discovered OSU had cut 16 acres of giant trees near Baker Creek in May of 2019, a whole new journey of discovery lay before me. Like the plot of some novel of deception and intrigue, the story unfolded in ways that felt both familiar and foreign: the forest manager (a proud CoF graduate) who adamantly denied they’d cut “old growth”…the phony claims that “signs of mortality” justified the cutting…the bizarre explanation that the road they’d cut into the adjacent old growth was for purposes of a “fire break access point”. With each revelation and excuse the dean and his minions only dug a deeper hole. OSU’s destruction of this ancient forest had sparked a firestorm of community distrust and anger. The lack of honesty and integrity in OSU’s response added fuel to the fire. It’s bad enough when leaders of our public university make such a profound mistake – it’s far worse when they lie and try to cover it up!

Advocating for positive change: After seeing the destruction of scores of ancient trees and and experiencing OSU’s deceptive response, I decided I had to do something about it. I organized a group of neighbors to form Friends of OSU Old Growth (https://friendsofosuoldgrowth.org/), an advocacy group dedicated to protecting older trees in the OSU forests. The scope of our mission also includes, “creating positive change in the College of Forestry”. Without fundamental changes to its outdated and misguided practices and priorities, the College will never be the “leader in forestry education” it claims to be. Our group was instrumental in getting The Oregonian’s Rob Davis to write his hard-hitting exposé, “Majestic Douglas fir stood for 420 years. Then Oregon State University Foresters cut it down” (1). The issue quickly received national coverage and was the lead story on CNN.com on July 23rd. The disconnect of our nation’s “leading forestry school” cutting down scores of centuries-old trees resonated deeply with people all over the country. It also severely undermined the College’s reputation – and trust in our public university.

The response from the broader OSU and Corvallis communities to our efforts has been overwhelming. People have a keen interest in protecting older forests and are deeply frustrated with OSU’s insular approach to managing what are generally perceived to be public forests. After all, OSU is a public institution, so the lands they steward belong to all Oregonians. In response to the old-growth cutting, OSU faculty, alumni, recreational users, and others who care about the forests have come together to demand change. It has been especially gratifying to receive the support of so many College “insiders” (including several emeritus/emerita professors) who have divulged details of the College’s dark past.

Industry bias & money corrupt the CoF: A former College employee (now a highly-regarded forestry consultant) described the misappropriation of more than 700,000 board feet of timber from OSU’s Blodgett Forest in the early 90’s. After reporting the theft to his boss (OSU’s Research Forest director), he was summoned to a meeting with the director and the dean of the College of Forestry. They fired him without so much as an explanation. He reported the crime and his punitive firing to the Oregon governor’s office. By the time state officials investigated, evidence of the theft had been erased from the College’s timber accounts.

An owner of a forestry consulting business stated he won’t even consider hiring OSU forestry graduates because they are so lacking in appreciation of ecological forestry values… an entire generation of CoF graduates are stumped when asked, “Who was Aldo Leopold?”

A former employee of the College told of research requests that were routinely used by the director and his staff to justify much larger harvests (against the wishes of the OSU researchers). Some told of other old-growth stands that had been cut in clear violation of markings and management plans. One person recounted how a former dean had declared to his staff that northern spotted owls nesting in the OSU forests were “irrelevant!” – directly contradicting OSU’s own spotted owl expert. A public records request later exposed this dean’s efforts to undermine ground-breaking research from an OSU grad. student – research that was a viewed as a threat to industry efforts to do salvage logging after the 2002 Biscuit Fire. The current Research Forest director, Stephen Fitzgerald, was one of six OSU professors who tried to suppress publication of the research in the prestigious journal Science.

I also heard numerous stories of staunch hardliners within the College who actively worked to further timber industry interests – at the expense of old-growth preservation and public health. A key emeritus professor on OSU’s 1993 forest planning committee fought to keep the old growth stands near Baker Creek and Sulphur Springs from being protected. One could say he shares responsibility for the 2019 old-growth debacle, as he planted the seeds of the conflict decades ago. This same guy led efforts to get “Agent Orange” chemicals (from the Vietnam war) used in forestry in the Pacific Northwest. When the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) threatened to ban these carcinogenic poisons in the late 70’s (due, in part, to a high rate of miscarriages near Alsea, Oregon), he and a group of OSU professors colluded with Dow Chemical to keep the pesticide (2,4-D) from being outlawed. These hardliners dominated the College for many decades, giving OSU a reputation as a tool of the timber industry.

Many of these old-timers are still active in the College to this day, influencing key decisions. One of them produced the draconian harvest scenarios in OSU’s original plan for the Elliott State Research Forest. [Update note: this emeritus professor’s plan to cut thousands of acres of older trees was embraced by the OSU team and eventually adopted by the State Land Board at their Dec. 8th, 2020 meeting. It was later passed into law during the 2022 session of the Oregon legislature, as part of SB 1546 establishing the Elliott State Research Forest].

OSU’s shifting response: As the story of OSU’s cutting of old growth gained national attention, the interim dean’s narrative changed in sadly predictable ways. His initial admission that it was a “mistake” and did not align with OSU’s principles morphed into conflicting variations. While he admitted that OSU had stopped following their 2005 Research Forest Plan in 2009 (a decade ago), he adamantly insisted they were “following the principles of their Plan… just not to a T” (The Oregonian). In a July 23rd, 2019, CNN.com story, he said, “For years we’ve had plans that these trees would be harvested, our mistake was in sticking to that (2005) Plan” (2).

Recently, the director of the Research Forests (Stephen Fitzgerald) gave a private tour of the site of the controversial old-growth cutting and insisted it was NOT a mistake to cut the trees. He also falsely maintained they were abiding by the conditions of their 2005 Plan (despite failing to meet the plan’s commitment to protect ALL northern spotted owl habitat in the southern zone of the McDonald Forest, where they cut the old growth). Members of OSU’s Elliott team have also reportedly said in their advisory committee discussions that it was NOT a violation of their plan to cut the old growth. These false assertions directly contradict the dean’s public narrative – and the facts. They tarnish the reputation and do a disservice to everyone associated with the College of Forestry.

The dean loves trees – and talking: In response to public concerns about OSU’s forest management, the dean and his staff held a public meeting (on August 28th, 2019) in Adair Village, north of Corvallis. The dean used the first half of the meeting to give a rosy and optimistic view of the College’s role in forestry education and research. He spoke of his childhood and how he loves trees. He portrayed forestry as the intersecting solution of climate change and sustainability. His lofty words and promises stood in stark contrast to how he and his staff have been managing the OSU forests (e.g. cutting ancient trees). This disconnect is a chasm separating OSU’s management of the forests from public values and expectations.

An angry public responds: When it was finally the public’s time to speak, the mood was tense. Dozens of neighbors unloaded decades of anger and frustration, telling how OSU has mismanaged the forests and disregarded their input. Citizens have clearly felt ignored and dismissed. To them, the old-growth cutting is just the latest in a long pattern of misappropriation of these public forests. Many participants expressed concerns about the unbalanced format of the meeting, following the traditional, “You have the questions, we have the answers” structure. Several of the participants noted they have advanced degrees and expertise in wildlife and forest ecology – yet their input has been repeatedly ignored by OSU’s forest managers.

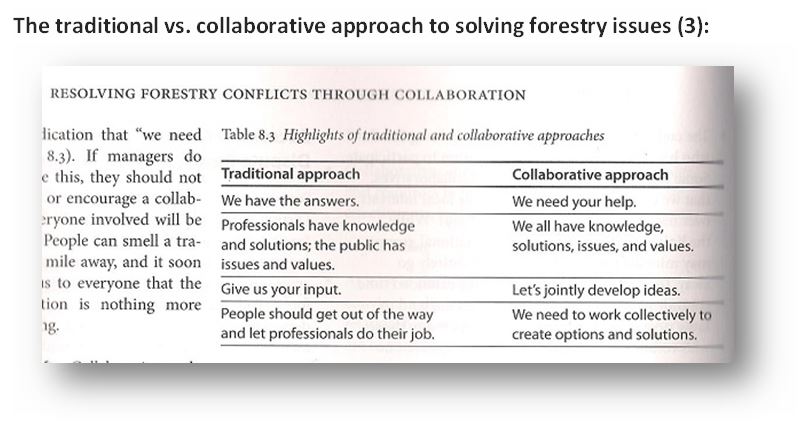

For decades, OSU has conducted forest planning following a misguided, traditional approach (as shown in the table below). While the dean has promised to follow a collaborative approach in the future, whether or not this is another empty promise remains to be seen. OSU needs to understand that true collaboration involves much more than soliciting public input, then rejecting what doesn’t fit their agenda!

Violations of the Plan are clear: Unfortunately for the dean and his Research Forest staff, the many violations of the 2005 Plan are as plain to see as the growing number of clearcuts in the OSU forests. An authoritative assessment by Debra L. and K. Norman Johnson (4) provides unequivocal documentation of the violations. It details how the cutting of old growth at Baker Creek (and numerous recent harvests) violated the Plan’s commitment to maintain the (1,585 acres of) nesting/roosting/foraging (NRF) habitat for northern spotted owls. The report estimates the total NRF has been reduced by ~166 acres (more than 10%) in the past three years alone. It also points to 10 clearcuts in the “South Zone” of the McDonald Research Forest that greatly exceeded the 1 to 4 acre harvest prescription allowed under the 2005 Plan. These are not minor oversights or adjustments – they are wholesale violations of the Plan, which is also OSU’s promise to the community. The Johnsons were involved in developing and implementing both the 1993 and 2005 Research Forest plans. Debra Johnson was the College’s GIS expert for the Research Forests for roughly a decade. Few people can speak with such authority and credibility when it comes to OSU’s forest management and planning. For the dean and his staff to insist the College is following the principles of the 2005 Plan is shamefully dishonest.

Policy evolution mirrors biological systems: Faced with such blatant disconnects and dysfunction, it is reasonable to ask how might one go about changing OSU’s deeply-entrenched and outdated approach to forestry. With timber industry funding and influence permeating the College (and paying the dean’s salary), is there any hope of substantive change?

Before considering these questions, it is helpful to take a moment to discuss the theory of change in large organizations. In Ecological Forest Management (3), the authors cite work showing that natural resource policies in the U.S. have evolved in ways that are very similar to biological systems:

Four Phases of Policy Development and Change

- Initial robust policy implementation followed by increasing rigidity over time as the policy matures and bureaucracies become committed to it.

- Challenge to the policy by activities based on differences between expectation and observation, which can create a crisis and lead to policy collapse.

- Catalysts for change taking action, helping create a bridge to a new policy.

- Development of new policy alternatives followed by policy selection and implementation, and the cycle beginning again. (5)

The authors observe:

“Initially robust policies become rigid, often with a single-minded emphasis on maximizing one aspect of resource management. The responsible agency becomes so invested in the policies, and the social forces that benefit from them are so powerful, that the agency cannot adjust as problems and circumstances change. Political and legal activists eventual take actions that result in policy disintegration, followed by individuals and groups whose ideas serve as catalysts for change”(3).

Following in the footsteps of the USFS: The authors of Ecological Forest Management also cite the highly relevant example of federal forest policy and over-harvesting, leading up to the Northwest Forest Plan of 1994. OSU’s College of Forestry seems to be following a similar trajectory:

With federal land managers having decided to prioritize ecological values over timber production nearly 30 years ago, one wonders why OSU still uses the university’s Research Forests as a “cash cow”.

After decades of overcutting by the timber industry and the systemic failures of the Forest Service and Congress to come up with meaningful protections for threatened and endangered species, newly elected President Bill Clinton got involved. The result was the 1994 Northwest Forest Plan which “placed conservation of biodiversity and watersheds first and timber harvest second”. An outside decision maker (President Clinton) delivered a new policy which forever changed the path of forestry in the Pacific Northwest (3). With federal land managers having decided to prioritize ecological values over timber production nearly 30 years ago, one wonders why OSU still uses the university’s Research Forests as a “cash cow”. Is this really “leadership in forestry education”?!

Parallels between the lead up to the NW Forest Plan and OSU’s failed attempts at forest planning are particularly relevant and powerful – at least up to the point of crisis and dysfunction! Just like the feds, managers of OSU’s Research Forests have had a long history of ignoring public input. Even worse, OSU has a history of abandoning its own carefully-developed plans. The last plan for the McDonald-Dunn was developed in 2005 and abandoned just four years later. The next one isn’t expected for at least three more years – a 17-year lapse. OSU followed a similar pattern with its Blodgett Forest. The College has also operated its Corvallis forests without an updated forest inventory or GIS staff for a full decade. How can a public entity managing 15,000 acres of land justify operating for so long without a plan and accurate forest inventory?!

Research Forests – the College’s “cash cow”: Revenue generation has clearly been given priority over other values in the management of the OSU forests – and in the planning process. With Research Forest employees (including the director) paid with logging revenue, they have a self-serving incentive to maintain logging volumes. This conflict of interest is at the heart of management decisions, betraying the public trust.

The forests have also been used as a reserve fund to cover unexpected shortfalls and fund the deans’ initiatives. The Oregonian reported, “$6 million in accelerated timber sales from the school’s forest near Clatskanie are being used to help defray cost overruns for …the Oregon Forest Science Complex“(6). What message does it send when our public university tears down a serviceable building and replaces it with one paid for by liquidating its “research” forest? These cuts happened after the Research Forest managers abandoned their innovative 1997 management plan for the Blodgett. The suspension of Research Plans for both the McDonald-Dunn and Blodgett Forests (last updated in 2005 and 1997 respectively) makes it clear that revenue is the primary driver of OSU’s forestry (not research and education). The failure to incorporate carbon assessments (as called for in the 2005 Plan) and adopt any meaningful provisions to combat climate change also reflect poorly on OSU’s forestry practices.

College leaders demonstrate lack of integrity: The lack of transparency and bias toward revenue generation has also characterized the dean’s “Tier 1 Advisory Committee” (T1AC). This group was tasked with developing the mission and goals for the next Research Forest Plan for the McDonald-Dunn Forests. The committee met for roughly two years, with little or no public notice. Their work was biased at the outset by a mandate from the former dean to come up with $2 million/year in timber revenue. When I asked the public rep. for the names of the committee members, he indicated the director had told him not to share information with me. The director’s actions constituted a “restraint of information” by a public employee – which appears to violate the law. It took three separate email requests to the dean just to learn the names of the committee members! Key questions about the committee’s work remain unanswered after repeated requests to the dean and OSU’s communication director. The refusal to answer fundamental questions clearly violates OSU’s own core values (7):

3) Integrity. We value responsible, accountable and ethical behavior in order to maintain an atmosphere of honest, open communication and mutual respect throughout the Oregon State community.

Seeds of change: Given the long history of mismanagement, the seriousness of the problems, and the power of vested interests, it seems doubtful change will come from within the College of Forestry. Until university leaders (i.e. the president and board of trustees) recognize the need for change, we are unlikely to see much progress. With a former Weyerhaeuser CFO and executive vice-president serving on OSU’s board (and their elite executive committee), I doubt we’ll see leadership from the trustees. Indeed, many Cof “insiders” and influential alumni share this view. The timber industry and federal land managers only changed course in the early 90’s when it was forced upon them by higher powers (president Clinton and Congress). Will we see OSU following a similar pattern?

With the growing urgency of climate change and the recognition that the timber industry is Oregon’s largest contributor of carbon emissions, changing the College of Forestry has never been more important. Public pressure and scrutiny of OSU’s forest management practices will continue to grow, as use of the forests and peoples’ expectations increase. OSU leaders will need to make fundamental changes if the College is to remain relevant and truly become the “leader in forestry education” it claims to be. The public rightfully expects to play a collaborative role in OSU’s forest planning – a change that threatens the regressive forces of the College. Citizens increasingly view OSU lands as a public resource – and they expect them to serve the greater good. With the power of social media, email, and the Internet, OSU will no longer be able to control the dialogue or narrative. The old-growth cutting controversy (and OSU’s bungled response) showed what happens when College leaders violate the public trust.

If the OSU administration is truly committed to changing the College of Forestry, it will need to lead the process. Here are some specific steps OSU leaders will need to take:

- Restore the management plans for the McDonald-Dunn and Blodgett Forests – and “follow them to a T“. This must be done with a strong, public commitment.

- Make the study and mitigation of climate change the highest priority for all College operations. Conduct detailed carbon assessments for all forestry operations. Stop all burning of logging slash piles. Make the research forests a leading example of ecological forestry management.

- Play the leading role in transforming practices of the timber industry to minimize climate change and prioritize ecological functions through education, research and advocacy. Exhibit this leading role by demonstrating the very best practices (prioritizing ecological values and carbon storage and mitigation) in the OSU research forests.

- Publicly commit to preserving ALL “late successional” reserves (i.e. stands over 80 years of age) on OSU lands – not just trees over 160 years old. With late successional forests largely protected on our federal forests, OSU should be matching or exceeding this relatively low bar. Start by changing the status of the Sulphur Springs stand to protect the remaining 36 acres of Old Growth.

- Disconnect timber industry funding from key positions within the College of Forestry, including the Dean’s endowment. This funding presents an enormous conflict of interest, biasing decisions at all levels of the College.

- Fully disclose all sources of funding for the College in an annual report presented to the public. This includes revenue from each timber harvest, donations to the endowments, funding of the new forestry building, research, and education. The public has a fundamental right to know where the money is coming from and where it is going.

- Change the planning process for the next Research Forest Plan to make it a truly collaborative process with public involvement. Make sure that the planning team is NOT biased toward revenue generation, but rather prioritizes ecological values and carbon mitigation and storage.

- Develop an independent assessment process with clear performance metrics to gauge the College’s compliance with their forest management plans. Publish the results. Hold a public meeting each year to present the results and discuss management plans for the coming year. Hold public tours on an annual basis to demonstrate management and research activities.

- Choose a new dean who is truly committed to positive change within the College of Forestry.

- The OSU president, executive committee, and board of trustees must provide active leadership and support for these changes – history has shown change will not come about without high-level involvement.

References:

(1): The Oregonian, https://www.oregonlive.com/environment/2019/07/majestic-douglas-fir-stood-for-420-years-then-oregon-state-university-foresters-cut-it-down.html

(2): CNN.com, https://www.cnn.com/2019/07/23/us/old-growth-trees-cut-oregon-state-trnd/index.html

(3): Ecological Forest Management, by Jerry Franklin, K. Normal Johnson, and Debora L. Johnson, 2018

(4): Damaging Ecological Resources Protected by the 2005 Forest Plan: Recent Harvests on the OSU McDonald-Dunn Forest,by Debora L. and K. Norman Johnson, https://friendsofosuoldgrowth.org/latest-news/

(5): Panarchy, by Lance H. Gunderson and C.S. Holling, 2002

(6): Old growth, new questions for OSU, by Rob Davis, The Oregonian, July 27th, 2019

(7): https://leadership.oregonstate.edu/trustees/oregon-state-university-mission-statement