With the isolation and confinement of the COVID-19 pandemic now upon us, many of us are sorely missing our connection with nature. We are keenly aware of how important our daily hike, run, or ride in the forest is for our physical health and mental well-being. With OSU’s McDonald-Dunn Research Forests serving the needs of well over 100,000 visitors every year, they are a key part of our community’s quality of life. Unfortunately, OSU has closed the Forests to all recreational activities in response to the pandemic. Their notice of March 23rd said the closure was, “in response to directives and guidelines from Oregon State University, the State of Oregon, and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.” The College of Forestry (CoF) website justified their decision by stating, “Immediately before the closure of the forest, several things were clear: the request to distance was not effective, resulted in the congregation of groups larger than ten people, and a respectful distance was not maintained when users were passing and crossing on trails or loading/unloading at trailheads.”

At a cursory level, one might be tempted to accept OSU’s judgement at face value. People ignoring health warnings during a pandemic is a serious matter. But a closer look raises some questions about the College of Forestry’s claims.

First, one wonders how exactly Research Forest staff communicated their concerns about social distancing. Between March 6th and March 20th, the College sent five “OSU Research Forest updates” to their extensive, community email list – yet none of them mentioned any concerns about the virus and the behavior of forest users. Their email of March 20th (just three days before the closure), focused entirely on “Keeping Trailheads Clean”. They wrote, “This week, we’ve seen increased use of the Forests, and unfortunately an increase in litter at trailheads, as well.” In the midst of the pandemic, with trailheads receiving extra high levels of use, OSU’s primary concern was…litter! Prior to the closure, there were no obvious warnings posted at trailheads. Even now, two weeks into the closure, the College’s Facebook page makes NO mention of the forest closures or concerns about the behavior of forest users. If OSU were truly concerned about the safety of forest users, why wouldn’t the CoF utilize their sizable email and social media presence to express their concerns?! Instead, their Facebook page is filled with promotional information about the College of Forestry.

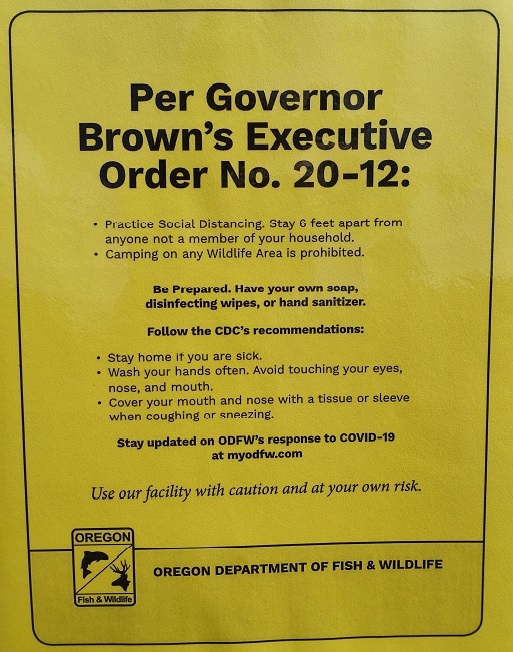

In typical bureaucratic fashion, OSU’s closure announcement makes it sound like their hands were tied – we had to do this because the State of Oregon and the CDC required it! For a more progressive alternative, one need only look at how the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) is managing their public lands. ODFW has chosen to keep local wildlife refuges open to the public, posting a simple, common-sense warning sign at the gates:

The wisdom of ODFW’s approach was clearly demonstrated on Sunday, as a relatively large volume of recreational users enjoyed a local wildlife area – while following common-sense COVID-19 guidelines. There were no ODFW or law-enforcement staff present, just people safely enjoying our public lands. If ODFW can do it, why can’t OSU?

It is important to keep in mind that nearly all of the OSU trailheads already limit usage through parking restrictions. Two of the most popular Research Forest access points, Oak Creek and the Lewisburg Saddle, only have parking spaces for a couple dozen cars. While OSU’s Peavy Arboretum can accommodate a lot more vehicles, it also has a lot more trails and forest roads to handle the visitors. Compared to the limited parking and access of Corvallis parks such as Bald Hill and Chip Ross, Peavy is much better suited to handling large numbers of people safely. In fact, the distributed nature of the Research Forests (with multiple access points) makes them an ideal area for public use during these difficult times. There are literally dozens of access points, from minor forest gates and neighborhood trails, to adjacent city parks and private forest lands. With a little leadership and flexibility from the OSU administration and Research Forest staff, the (11,500-acre) Forests could safely accommodate large numbers of visitors every day despite the pandemic.

Here are some specific, common-sense alternatives that OSU’s Research Forest managers could choose to implement:

- Use email messages and Facebook page to communicate safety guidelines and express concerns about the behavior of recreational users.

- Post common-sense warning messages at Research Forest access points (similar to the ODFW signs).

- Close restroom facilities (or post warnings) to limit exposure at these contact points.

- Limit parking/access (e.g. by closing off sections of parking, asking people to limit their use to 2 visits per week, or avoid high-use times, trails, and trailheads).

- Encourage access by pedestrians, runners, and cyclists (this could be done even with the current parking closures and would provide safe and sustainable access for thousands of Corvallis residents and forest neighbors).

- Ask that forest users wear masks at parking areas and trailheads to minimize the risk of exposure.

The College of Forestry’s announcement also justifies the closure of the Research Forests by explaining that, “As a result [of COVID-19 concerns], a majority of our staff are now working from home and are unable to adequately maintain our recreational trails and facilities at a time where increased use would be likely.” Having frequented the McDonald Forest trails for decades, I find this justification especially disingenuous. Many of the trails were built by volunteers long before the current generation of Research Forest staff were hired. For years, maintenance was infrequent and largely left to trail users and volunteers. Despite limited funding and no OSU trail crews, the condition of the trails met the needs of most users year-round. Other than the occasional need to cut a downed tree, the recreational trails of the McDonald Forest would do just fine without OSU’s active management. If some critical maintenance or safety issue were to develop, OSU could simply close a trail until pandemic restrictions ease.

What bothers me most about OSU’s forest closure is that it fits a pattern of poor management and an overzealous desire to control what Research Forest managers clearly perceive as their domain. The Director of the Research Forests often speaks of them as “community forests”. But when it comes to management decisions – whether it be cutting old growth or shutting down the forest – the public is entirely excluded from the process. And when faced with perceived threats to their sovereignty of the Forests, OSU has often wielded a heavy hand. Illegal trails and violations of logging closures are met with video cameras, patrols by law enforcement, and threats of prosecution.

Last year, OSU put substantial effort into catching people making unauthorized trails in the forest. A friend who had made a narrow trail on an old logging track was caught using video surveillance. When the armed forest deputy showed up at her home and confronted her, she tried to explain and defend her actions. The trail allowed neighbors to avoid walking on a road with limited visibility. She had called OSU to make sure her trail wouldn’t jeopardize any research projects. She told him she had built trails for the Forest Service for many years and had been careful to minimize impacts. In response, the deputy threatened to haul her off in handcuffs (in front of her daughter) and told her she needed, “to be humbled”. The Research Forest Director later summoned her to a meeting where she was told she’d be prosecuted by the District Attorney. The Forest Director said she’d have to make a donation to OSU’s trail fund, do “volunteer” work decommissioning her trail, and advocate against illegal trail-building in our neighborhood. After a significant amount of community pressure, Research Forest managers reluctantly dropped the prosecution (though the trail still remains closed).

Last summer, OSU directed the same sheriff’s deputy to patrol the site of the old-growth cutting in an effort to catch folks who were visiting the clearcut on weekends. Nearly a month after the official closure date was past and logging had concluded, the deputy caught two kids who had hiked to the clearcut through the adjacent forest. He issued citations for criminal trespass and threatened to haul them to the juvenile detention center. Despite several requests from the parents to drop the case, OSU officials claimed they were powerless to intervene (even though, as the property owner, they could have simply declined to press charges). The charges were eventually thrown out by the D.A.’s office, but only after months of delay and significant legal expenses on the part of the families. This same deputy has recently been sighted patrolling our rural neighborhood (and is reportedly issuing $450 tickets to people caught violating OSU’s forest closure). Like Carnegie hiring Pinkerton thugs to break strikes in the steel mills, OSU funds the Benton County Sheriff’s Department for the services of their rabid deputy.

By using law enforcement and an aggressive response to what are arguably minor policy violations, OSU’s forest managers have alienated the very public that funds them – and which they should be serving. Research Forest managers claim they lack resources to enforce social-distancing violations related to the pandemic, but they clearly failed to communicate their concerns to the community and consider alternative solutions. Their sudden closure of the Forests seems arbitrary and unjustified. If OSU’s College of Forestry is to have any hope of rebuilding public trust, University leaders should reverse their short-sighted closure of the Research Forests.