(This piece was published in the Corvallis Advocate on July8th, 2025. You can find the article here. Please consider supporting the Advocate, our only local, independent news source!)

On June 18th, Oregon State University released its draft management plan for the McDonald-Dunn Forest, the first update in 20 years. College of Forestry leaders provided the public a scant 30-day period to review and comment on the 171-page plan. For those who’ve followed OSU’s multi-year, contentious planning process, the scheduling of the public review period at the start of the summer recess has triggered yet more distrust. It is hard to imagine better timing if OSU were looking to diminish public engagement.

OSU has not announced a single public meeting to present the draft plan to the Corvallis community. This is in itself, a remarkable low for a public university managing public forests. For a plan of this complexity and one expected to last a decade or more, a 30-day comment period is completely inadequate. For comparison, state and federal agencies generally allow 45-60 days for public comment on natural resource plans covering a much shorter time period.

With nearly 200,000 visits to the McDonald-Dunn each year, recreational users are the predominant forest stakeholder group. OSU should have respected our community’s deep ties to the forest by providing for an extensive plan review. This oversight seems especially clumsy for a College that recently concluded a multi-year forest planning effort involving the Elliott State Research Forest. During that process, OSU was repeatedly criticized for not following standard public review protocols. It seems college leaders have a difficult time with this concept: shortchanging the public only breeds more distrust.

The central theme of OSU’s draft plan is a perpetuation of clearcut forestry (euphemistically referred to as, “even-age rotations”) across 40% of the McDonald-Dunn. The size of clearcuts in the southern portion of the McDonald Forest will increase dramatically from the 4-acre limit of the 2005 plan. The new plan will allow clearcuts of up to either 80 or 40 acres in size (for short-rotation vs. long-rotation cuts) throughout much of the forest. This is certain to spark increased community outrage as recreational users encounter larger clearcuts along the most popular forest roads and trails.

Under the new plan, 23% of the McDonald-Dunn will be actively managed as, “multi-aged, multi-species” forest. This land will be subject to various logging treatments, such as “variable retention regeneration harvests” (which are not defined, but can have as little as two trees left standing per acre by law). Based on OSU’s past practices and industry standards, one should assume less than 10% of the overstory trees will be spared. You can think of it as “clearcut light”. These harvests will be limited to 40 acres in size. Another ~10% of the forest will remain in “long-term research”, with nearly 8% of this falling under the College of Forestry Integrated Research Project (CFIRP). This research involves cutting a third of the timber volume in small patches every 20-30 years.

In total, 71% of the McDonald-Dunn will continue to be managed following industrial forestry practices, with the majority of it subject to clearcutting.

OSU’s draft plan will allow old-growth stands to be treated for a variety of discretionary reasons, including “public safety” and “fuels management”. College leaders justified the 2019 old-growth cutting, shown here, with false claims of risk to recreational users.

While the draft plan promises accountability, it relies on the relatively low bar of the Oregon Forest Practices Act (OFPA) as the primary guide of forestry activities. That seems particularly odd for a College that strives to be a global leader. Other than the OFPA, there appear to be few, if any, legally enforceable constraints. The plan will continue OSU’s pervasive use of herbicides and the burning of logging slash, which is a major source of cancer-causing particulate and greenhouse gas emissions.

Reading the plan, you wouldn’t even know there’s an entire field called “ecological forestry” which was pioneered by OSU’s esteemed former faculty. Instead, the plan deliberately promotes misleading industry talking points. The importance of sequestering forest carbon is downplayed, while polluting biomass energy technology is promoted as a “renewable energy source”. This is not so much a forest management plan as a thinly-veiled attempt to advance a pro-timber logging and research agenda.

On the conservation side, the draft plan designates 10% of the forest as “ecosystems of concern”. This is comprised of oak savanna and prairie/meadow ecosystems, as well as riparian zones. The plan devotes nearly seven pages to the stewardship of native oak and prairie habitats, which will be undertaken in partnership with Tribal Nations. How this will work in practice remains to be worked out, though the implications are huge. One wonders if Tribal Nations will be satisfied with OSU’s extractive management of their historical homelands.

The draft plan will set aside 10% of the McDonald-Dunn as, “late-successional forest” (LSF). This includes formerly-protected old-growth reserves, as well as additional sections of older forest. While this is an increase from the 3.5% of protected reserves in the 2005 plan, the expansion comes with a deliberate removal of protections. It abandons the 160-year age limit for cutting individual old-growth trees and stands. OSU’s foresters will now have broad discretion to manage old-growth stands for, “public safety”, “fuels management”, and “invasive species control”.

The plan says, “These former reserve areas will be stewarded as needed to maintain older-forest structural and compositional diversity and to provide for public safety, (e.g., hazard tree removal, fuels management) and invasive species control. Younger stands newly added to this strategy may need more active operations in the near term (e.g., variable retention harvests) to promote the development of older forest conditions.”

One can easily imagine OSU foresters once again claiming that an entire stand of old growth must be cut down because it poses a danger to recreational users, violates OSHA rules, and has “signs of mortality”. It is telling that the plan only devotes a couple of pages to the subject of older forests, and half of that lies in the, “Timber Harvest Schedule” section.

The language of the draft plan echoes OSU propaganda used to justify cutting dozens of large, old trees in last summer’s ‘Woodpecker’ thinning project. These trees were part of a thriving older forest ecosystem.

Just as concerning is the language which will allow OSU to “treat” (read as log) the newly added sections of older forest to “promote the development of older forest conditions” and create, “structural and compositional diversity”. This should sound alarmingly familiar, as College leaders used this same language when they sought to justify last summer’s controversial cutting of older trees near Peavy Arboretum. OSU foresters will now be able to thin a majority of trees in these older stands under the guise of “restoration”, following the example of our state and federal forest managers. It is as if this provision of the plan was specifically designed to permit the cutting of older trees that were previously off-limits to logging.

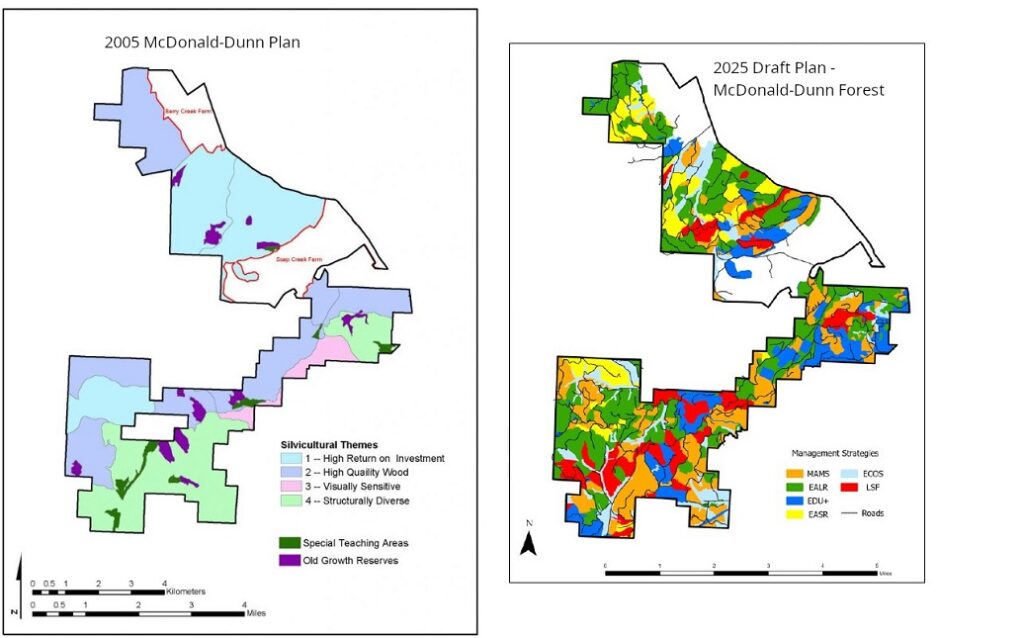

A comparison of the 2005 McDonald-Dunn Plan (at left) and OSU’s new draft plan (at right) shows a dramatic change in how the forests will be managed. The fragmented approach of the draft plan seems to ignore both watershed boundaries and recreational priorities. (Abbreviations are as follows: MAMS – multi-aged, multi-species; EALR – even-aged, long rotation; EDU+ – long-term learning and non-forest; EASR – even-aged, short rotation; ECOS – ecosystems of concern; LSF – late-successional forest; both maps courtesy of OSU)

With years of planning and public involvement drawing to a close, the draft plan provides us with the first geographical information disclosing how the proposed forest classifications will affect the landscape. What we see is a forest divided into a complicated matrix of “management strategies”. This is the opposite of a holistic approach, where watershed boundaries and ecological considerations guide forest stewardship. It is also a dramatic change from the previous plan with its four, large “silvicultural themes”.

In the past, large clearcuts were concentrated in the relatively remote Dunn Forest, while the most popular areas of the McDonald Forest were – or should have been – protected from extensive clearcutting. Under the new plan, clearcuts of 40-80 acres in size (shown in green and yellow in the above map) will be allowed across much of the forest. The “mixed-age, mixed species” areas (shown in orange) will also be subject to extensive forest management (thinning and eventual harvest). The maps are a vital component of the planning process and should have been presented at last year’s “community input sessions”. The dean’s “Stakeholder Advisory Committee” was also hindered in their work by the absence of geographical information.

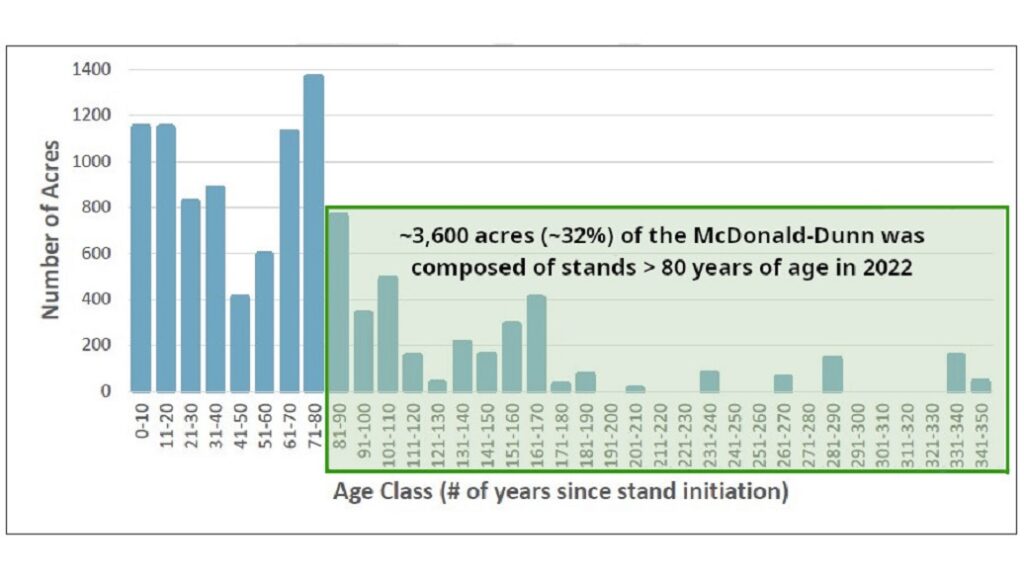

Number of acres of Douglas-fir according to age class distribution in the McDonald-Dunn Forest as of 2022. Protecting all “mature and old-growth stands” (i.e. over 80 years of age) would only remove about 1/3 of the forest from active timber management. (OSU chart modified by Friends of OSU Old Growth)

It is disingenuous of the OSU planning team to claim the draft plan incorporated public input when an overwhelming majority of citizens strongly opposes clearcutting and desires expansive protections for older forests. It is telling that of the 15 management scenarios evaluated by the planning team, the maximum amount of older forest they considered protecting was only 19%. A detailed analysis of the draft plan’s “age class distribution” shows that approx. 3,600 acres, or 32%, of the McDonald-Dunn was composed of forest over 80 years of age in 2022.

Protecting the oldest third of these public forests from logging would align with community values and the scientific consensus reflecting the critical role of mature and old-growth forests in mitigating climate change. It is revealing that the final suite of management scenarios presented to the dean all had the same allocation of older forest – 10%. In fact, four of the six land allocations were exactly the same. In this way, the draft plan seeks to present the illusion of choice when the outcome appears to have been pre-determined.

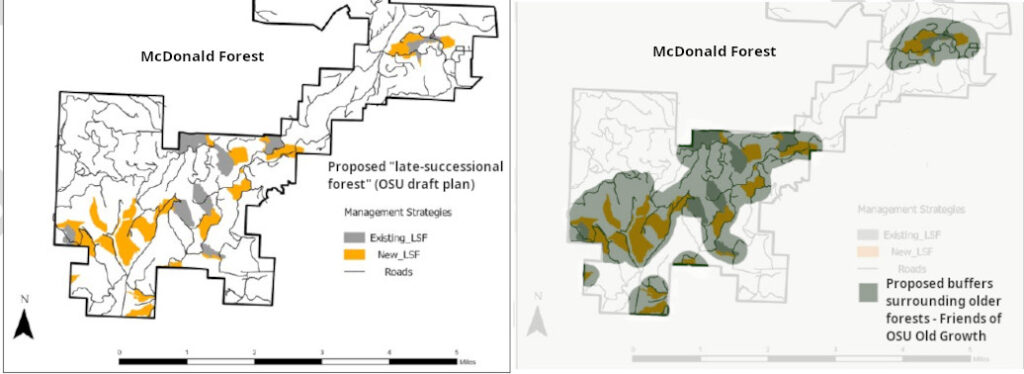

The draft plan’s map of older “late-successional forest” (at left) lacks detail and fails to provide buffers or take into account watershed boundaries. A holistic approach (shown at right) would have provided substantial protective buffers (edited map courtesy of Friends of OSU Old Growth)

The dean and his planning team must think that setting aside stands over 160 years of age from logging represents a major conservation concession. In reality, it shows a profound lack of understanding of both community values and forest ecology. The additional acreage of older forest (shown in yellow above) is only about 6% of the forest.

What stands out most profoundly is the complete lack of buffers surrounding these older stands. There is strong scientific support for the need to maintain buffers around older forest for a host of ecological reasons. Buffers help maintain biodiversity and wildlife habitat by providing connectivity and serving as refugia for sensitive species. They also support climate resilience by creating cooler, more stable microclimates compared to younger plantations – which have a significantly higher fire risk, as well.

Had OSU followed well-established science, it would have included substantial buffers to protect these older stands as shown in the map on the right.

Climate change meets insularity meets outdated agenda

One of the draft plan’s most disappointing aspects is its lack of serious commitments in the area of climate change. The language of the plan reveals an arrogant and unrealistic response to climate change with statements like, “Threats such as climate change…will be actively managed and mitigated as appropriate.” OSU’s forest planners devoted just over two pages – 1% of the draft plan – to the section dealing with climate change.

By echoing industry propaganda about the storage of carbon in long-term wood products, rather than in older forests, the authors of the draft plan seem to be deliberately targeting decades of important climate research by OSU’s own experts.

The plan also promotes a deeply-flawed research paper by the former forest director which concluded that clearcutting and frequent thinning is the best way to optimize forest carbon. It also cites a recent essay by the dean which downplays the sequestration of forest carbon, arguing that fossil fuel emissions are a much bigger problem. The inclusion of such obvious bias and advocacy in the draft plan reflects poorly on the scientific integrity of the College of Forestry and OSU’s academic reputation.

OSU’s draft plan for the McDonald-Dunn reveals a College of Forestry that is stubbornly clinging to its extractive roots. Its perpetuation of clearcut forestry across much of this public forest has little relevance for industry and is profoundly out of touch with societal values. Its promotion of industry propaganda at the expense of decades of OSU research on forest carbon reveals an insidious and misguided agenda.

The adoption of this deeply flawed plan will further diminish public trust and tarnish OSU’s reputation. It is time for OSU leaders to change course and embrace ecological stewardship of this public forest.

You can help, July 18 deadline

You can submit your comments on OSU’s proposed forest management plan by emailing their planning team at McDonaldDunnPlan@oregonstate.edu. You can also email OSU’s administration at trustees@oregonstate.edu. You can find more information about the draft plan here, on the Friends of OSU Old Growth website.

By Doug Pollock, founder of Friends of OSU Old Growth. This is a guest commentary, it may or may not reflect the views of The Corvallis Advocate, or its management, staff, supporters and advertisers.