President Murthy Withdraws OSU from ESRF Management: On November 13th, 2023, OSU President Jayathi Murthy published a letter announcing OSU’s withdrawal from their planned management of the Elliott State Research Forest (ESRF):

“It is with great disappointment that I share the unfortunate news that, at this juncture, I am not prepared to make a recommendation to Oregon State University’s Board of Trustees that they authorize OSU to participate in the management of the Elliott State Research Forest (ESRF).”

For those of us who’ve fought OSU’s ~5-year effort to impose their antiquated, timber-centric research framework on what was supposed to become our nation’s largest research forest, this news was both an enormous surprise – and a vindication. For several years, we’ve been criticizing a litany of egregious violations of basic science, the public process and public trust. This includes:

- A “research plan” that targeted older stands, lacked scientific and social relevance, and was rejected by their own, renowned experts

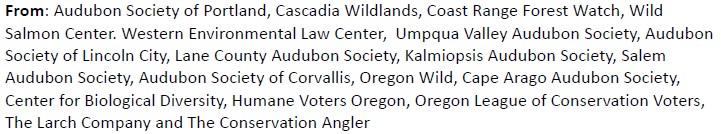

- Continued fragmentation of the Elliott via clearcut, rotation forestry on more than 10,000 acres of the forest (in perpetuity)

- An insular, autocratic governance plan that gave broad powers to OSU, The Oregon Dept. of State Lands (DSL) and their industry cronies (instead of elected officials).

- Deliberate, undemocratic provisions of Senate Bill 1546 (orchestrated by the DSL and OSU lawyers)

- Violations of the public process (inadequate review periods, failure to follow the Oregon Public Meeting Law, the selection of biased committee members without public notice or participation)

- Ignoring the bulk of public comments which condemned OSU’s approach and prioritized protection of the Elliott

Blame Aimed at Other Groups & Constraints: President Murthy’s letter points the finger of blame at a number of other groups, while steering clear of OSU’s role in this debacle. I will take a closer look at her letter and OSU’s role below. What is undeniable is that this marks a colossal failure on the part of the dean and his Elliott team. It is also arguably the greatest setback in the modern history of the College of (de)Forestry.

Over the course of nearly five years, OSU has devoted significant resources to this Elliott endeavor, at an estimated cost of $15M. Dozens of employees, from Forestry to Finance, from the trustees to graduate researchers, and from the legal department to Marketing and Communications have been involved in this effort. To see it all miraculously implode at this late stage is truly extraordinary. One can only hope College leaders and the OSU administration do some serious soul-searching and change their antagonistic approach to the conservation community. Transparency, accountability, and some serious humility are what’s needed to rebuild public trust.

President Murthy’s letter offers substantial clues into what led to the collapse of OSU’s Elliott efforts. But first, let’s be clear: this was NOT something the dean or president wanted. The president expressing her “great disappointment” and describing it as “unfortunate” makes that clear.

The dean’s letter, in contrast, has a much more optimistic tone: “…OSU and the College of Forestry remain ready to engage in the work of planning an Elliott State Research Forest on a recalibrated course…“. One gets the sense he still hasn’t comprehended the enormous ramifications of the president’s decision. All of this leads me to wonder what future the dean has at OSU. Having assumed leadership of OSU’s Elliott efforts when he joined OSU in June of 2020 (over three years ago), the dean must now bear the full responsibility for this failure.

OSU’s Official List of Elliott Problems: President Murthy’s letter identifies a number of factors that caused her to pull the plug on OSU’s Elliott endeavor:

- public opposition to the Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP)

- opposition from the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians (CTCLUSI)

- recent public and industry stakeholder comments criticizing OSU’s forest management plan (FMP) for the Elliott

- pressure from the governor/Oregon Land Board to limit timber harvest volumes

- constraints on “research” (timber harvests) that would be imposed via potential monetization of carbon credits

- concerns about financial self-sufficiency and revenue generation

It is worth examining some of these factors in more detail.

A broad coalition of Oregon environmental groups was highly critical of the Elliott HCP

HCP Triggers Broad Opposition from Conservation Groups: In a (27-page) report from Jan. 10th, 2023, a coalition of 18 environmental groups expressed their significant dissatisfaction with the HCP and draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the Elliott. In their letter to the US Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service (which administer the HCP process), the groups detailed the many scientific shortcomings and discrepancies in the HCP. A substantial portion of the misunderstandings appears to have arisen from commitments made (but not kept) by OSU.

The coalition also criticized OSU’s plans to log older forests as a justification to study impacts to endangered marbled murrelets (a concern I first raised years ago) :

To be clear, the real problem is not OSU’s management plan (FMP), but rather their 2020 research plan for the Elliott. The dean and his team never fixed the profound flaws that Dr’s. Franklin and Johnson so powerfully articulated. Doing so would have involved a radical restart of their entire project. First, a comprehensive analysis would have had to be done to determine the most relevant research needs for society and industry. Second, they would have had to abandon their antiquated “working forest” approach (called “Triad”). Clearcutting under the guise of research on more than 10,000 acres of the Elliott just doesn’t fit with the concept of “our nation’s largest research forest”. In short, the FMP and the scientific credibility of the Elliott are built upon the crumbling foundation of their 2020 research plan.

Land Board Reiterates Annual Harvest Limits: Pressure to limit annual timber harvests in the ESRF was another key factor in president Murthy’s decision. In a recent letter from the governor’s senior natural resources advisor, Geoff Huntington, the Oregon Land Board reiterated harvest limits in the ESRF:

“Harvest Volume. The HCP, Forest Management Plan, and Financial Plan should be calibrated to an anticipated annual harvest volume of approximately 17 MBF [million board feet] per year…The target is not an absolute ceiling…but that variability cannot be averaged over decades—or even multiple years—in order to meet the target of 17 MBF per year…It is worth noting that prior to this process being initiated, a harvest cap of 25 MBF proposed by ODF was rejected and led to the stand-off the research forest mission was originally designed to resolve.”

“Harvest Acreage Limit. The cap on annual acres subject to harvest was also subject of intense negotiations that established stakeholder expectations for management of the forest by the ESRF Authority…management objectives should not deviate significantly from the agreed upon 1,000 acres (which was an increase from the 736 acres identified in the 2020 Proposal). Even though that original cap was expressed as an “annual average,” there was no expectation on the part of stakeholders or the Land Board that calculation of this “average” would stretch over an extended time period. Forest management objectives must be tailored to recognize…the harvest volume commitments as [legal] sideboards within which the research design and forest operations are conducted.“

While one might be tempted to interpret Huntington’s letter as an affirmation of annual harvest targets, the context and language make it very clear that the Land Board is most concerned about OSU exceeding these harvest limits. The 17 MBF/year harvest cap was a key factor in both stakeholder buy-in and OSU’s revenue models. Huntington also called out the ~36% increase in logging acreage from what OSU proposed earlier. Despite this agreement, some within OSU have been pushing for substantially more logging (reportedly up to 30 million board feet per year). In response, the Land Board is saying, “Don’t even think about it!“

Carbon Credits Would Restrict (Logging-based) Research: president Murthy’s letter makes it clear that OSU is very concerned that limits on logging might impact their management of the ESRF. She claims OSU’s concerns are focused on, “the health and resiliency of the forest…the dynamic nature of both forest ecosystems and adaptive management…and the integrity of a functional replicated research design as described in the ESRF Research Proposal.“

For those of us who’ve followed OSU’s Elliott process from the start, the language in the president’s letter sounds like something from the regressive forces within the College of (de)Forestry. Reading between the lines, one hears echoes from the past:

“We are the experts and we won’t accept anything that limits our ability to log this forest into better health!”

Concerns about Financial Viability: With start-up costs for the Elliott State Research Forest estimated by OSU to be roughly $35M, president Murthy’s concerns seem warranted. The Land Board has made it clear that OSU won’t be able to log their way out of this start-up deficit.

It is important to point out that OSU’s approach to the ESRF has often been criticized as being too costly. I recall one of their estimates calling for 35 trucks to be dedicated to the Elliott. It is hard to imagine why so many vehicles would be needed at one time. The large number of OSU staff associated with the ESRF also seemed excessive when many of the services could be outsourced to local contractors.

The same criticisms apply to OSU’s McDonald-Dunn research forests, near Corvallis, where OSU’s research forest director makes well over $100,000/year and the forest manager makes more than $80,000/year. The forest manager handles tasks like putting plastic on slash burn piles. Surely that kind of work could be done much more affordably by forestry students or independent contractors. It is important to keep in mind that the added cost of benefits and “other personal expenses” (OPE) means that the true cost of OSU personnel is substantially higher than the salaries alone.

The Future of the Elliott: While the future of the Elliott State Research Forest may now seem a little uncertain, this enormous setback for the College is a very positive and fitting result.

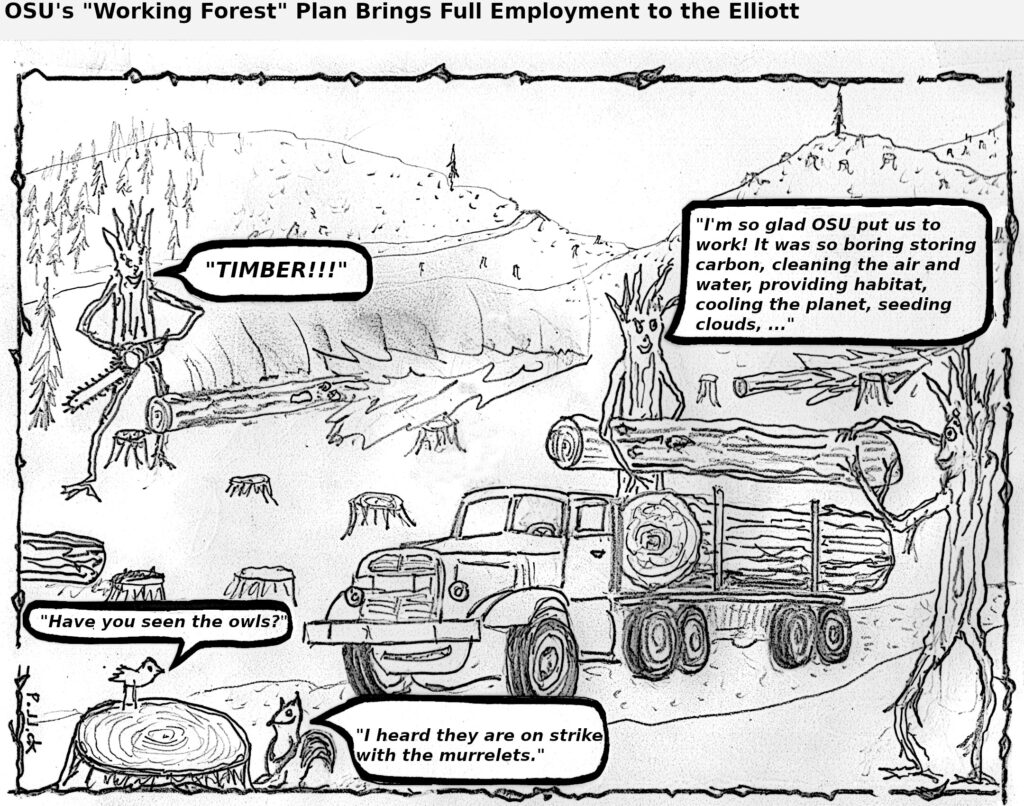

The roots of the College’s Elliott failure began with OSU’s cutting of old growth in 2019. That profoundly misguided decision by OSU’s research forest director exposed the regressive tendencies of the College of (de)Forestry to a national audience. As I pointed out right from the start, the issue was much bigger than the destruction of ~16 acres of ancient forest. The real question was, “How can we trust a public university that cuts its own old growth to manage our nation’s largest research forest?” The answer was and remains: “We can’t!“.