In my previous blog piece, I outlined three recent land transactions involving the McDonald-Dunn Research Forests (public forest lands stewarded by OSU). That piece focused primarily on a (~277-acre) parcel of land that Starker Forests, Inc. donated to OSU. This post will focus on the 2nd parcel of land, the Spaulding Research Forest (managed by OSU for more than a century, but donated to Starker Forests in September, 2023).

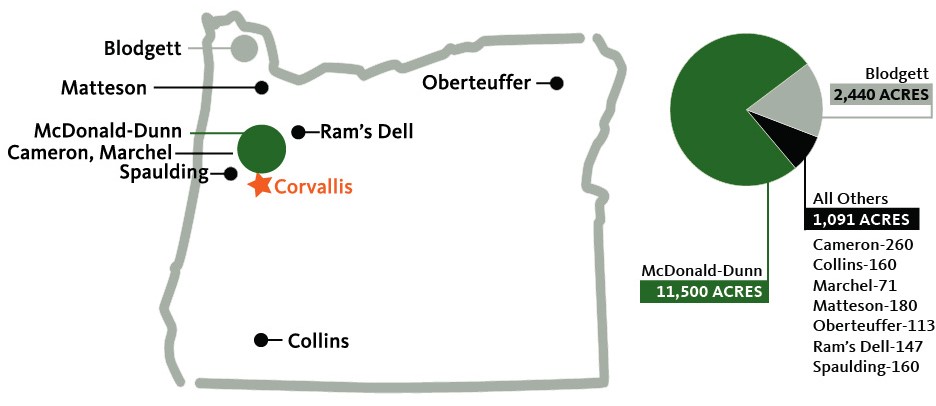

Before getting into the details, it’s important to provide some background and perspective on OSU’s Research Forests. Until recently, OSU’s College of Forestry managed ten forests located across the state. This map shows the general locations and sizes of these tracts:

OSU’s Research Forests. The largest by far is the McDonald-Dunn (located near Corvallis). The Spaulding no longer exists, after OSU donated it to Starker Forests (in exchange for the Baker Tract, now part of the McDonald Forest). (map courtesy of OSU)

The history of these tracts is relatively diverse, with many consisting of donated lands, while others, like the Dunn, were purchased with funds donated by citizens, as well as university funding (public money).

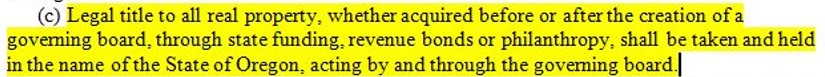

While generations of College leaders have tried to promote the idea that these forests belong to the College of Forestry, the legal reality is distinctly different. State law (ORS 352.025 (2) (c)) clarifies that the State of Oregon holds the titles for the University’s real property (land and improvements). Since the state holds the titles, it follows that these are public lands (belonging to all Oregonians). The ORS also states that the “governing board” (OSU Trustees, including the president) is responsible for the oversight of these public lands.

Oregon Revised Statute (ORS) 352.025 clarifies that the State of Oregon holds the titles of all OSU properties. This means OSU’s Research Forests are public lands.

OSU’s (former) Spaulding Research Forest is located in the Corvallis Municipal Watershed close to Marys Peak. The adjacent, older forest provides habitat for endangered Marbled Murrelets and Northern Spotted Owls. Unfortunately, College leaders have operated this forest as a short-rotation tree farm for most of its 100+ year history. (photo courtesy of OSU)

The concept of “Research Forests” could be the subject of a lengthy blog post all by itself. While our elected leaders and state bureaucrats react like Pavlov’s dog when they hear College leaders profess their dedication to research, the Elliott State Forest process showed that research often comes with an agenda. For example, OSU’s proposed research on Marbled Murrelets consisted of a plan to log the Elliott’s Murrelet habitat to see how much cutting the imperiled birds could tolerate. Sadly, such timber-centric research is a hallmark of OSU’s College of Forestry, which has promoted the industry’s agenda for generations.

The College of Forestry’s webpage describes the purpose of the (former) Spaulding Research Forest. While it has historically been managed for timber-related research, its location in the heart of the Corvallis Watershed provided an opportunity for far more progressive stewardship.

Regardless of what type of research College leaders choose to promote, the OSU president and trustees are bound by clear and rigorous ethical standards (at least on paper). Under the “Basic Responsibilities” of the trustees’ bylaws they are required to “preserve and protect its assets for posterity“. The bylaws also state trustees must “Conduct the board’s business in an exemplary fashion and with appropriate transparency,…adhering to the highest ethical standards…“

It is hard to understand how the dissolution of a public research forest (with a 100+ year history) preserves and protects the university’s assets for posterity. It is difficult to see how allowing these land transactions to be finalized without any public notice or involvement provides the transparency and public accountability dictated by state law (e.g. as described in ORS 352.025). How can the president and board chair refuse to respond to (or even acknowledge) questions about these matters?

If the president and trustees truly did not consider these land transactions (as associate dean Ober claimed in her email to me), it shows a supreme dereliction of their fiduciary responsibilities.

With different management priorities, OSU could have restored old growth habitat (like this nearby section of the Corvallis Watershed below), instead of perpetuating industrial forestry practices in the Spaulding. Future research opportunities are now lost, with the transfer of this public forest to a private company.

I wonder what the ancestors of the Kalapuya, the original inhabitants of these forests, would think about OSU’s stewardship of their former lands. Did OSU invite Tribal members or Indigenous students to weigh in before deciding to privatize the forest? In this age of climate change and ethnic diversity and awareness, OSU’s decision to eliminate this public forest seems decidedly out of touch.