Pay much attention to forestry issues and, sooner or later, you’ll run into experts (many of them OSU-trained) who claim that forest management (mostly logging) is the key to restoration. Whether it be wildfire prevention and recovery or converting even-aged stands to ecologically-diverse forests, cutting trees is promoted as the solution. With practices like “variable-density thinning” (cutting trees in an uneven pattern), foresters strive to accelerate the recovery of natural forest ecosystems. The underlying assumption is that we can heal and restore the forest better and faster than nature can on its own. There’s both tremendous arrogance and a seductive appeal in that way of thinking. Man’s folly in manipulating nature has left a long trail of destruction, littered with countless extinctions and invasive species. At the same time, there’s a very real need to restore the millions of acres of public forests that have been converted to even-aged tree farms. Who wouldn’t like to find a way to re-establish a complex forest ecosystem in decades, rather than centuries (or millennia)? Whether restoration-through-cutting is just more hubris or can actually benefit nature remains to be seen.

Unfortunately, the experts and their approach to forest management often serve a contrary agenda. With timber money and influence corrupting all levels of our Oregon governance (as well as OSU), it’s predictable that restoration and stewardship will be used as an excuse to justify logging. This appears to be the case with a major thinning operation planned for the Corvallis Watershed starting in mid-April. Before getting into the details, I need to provide some background information.

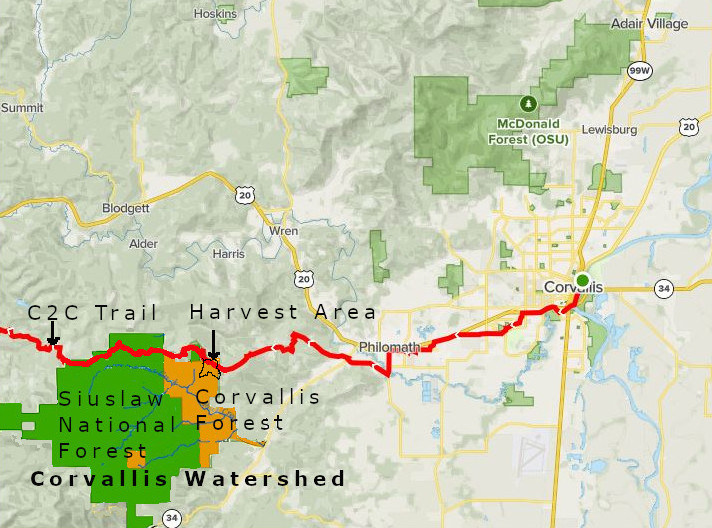

If you live in Corvallis, you probably have a vague understanding that some of your water comes from a pristine source – a ~10,000-acre, forested watershed, located on the east flank of Marys Peak. The Corvallis Watershed is comprised of the 2,352-acre Corvallis Forest (owned by the city), plus another ~8,000 acres of the adjacent Siuslaw National Forest (administered by the US Forest Service). The Corvallis Forest was purchased in the early 1900’s to protect our water supply. With the exception of the new Corvallis-to-the-Sea (C2C) Trail corridor, the watershed is generally off-limits to the public.

Most folks are surprised to learn that the Corvallis Forest has approx. 750 acres of forest that has never been logged. According to the Corvallis Forest Stewardship Plan (CSFP), this makes it one of the largest concentrations of non-federal old growth in Oregon. For comparison, this is more than twice the amount of old growth in the OSU Research Forests! The forest provides important habitat for two federally threatened species, the northern spotted owl and the marbled murrelet (which is also listed as endangered in WA, OR, and CA).

The Corvallis Watershed provides roughly a billion gallons of drinking water to our community each year. During all but the high-demand summer period, the watershed supplies ~ 1/3 of Corvallis’ domestic water needs. The rest comes from the Willamette River. If you consider that upstream communities like Eugene and Springfield pump their treated sewage effluent into the river, the value of having a dedicated, natural watershed becomes clear. The Corvallis Forest doesn’t receive agricultural, industrial or domestic wastewater discharges. Other than the impacts of forestry operations, the watershed is largely untouched and off limits.

This amazing stand of old-growth forest is only a few hundred feet from the planned thinning in the Corvallis Forest.

I first learned of the city’s upcoming logging plans when a watershed neighbor, Malcolm Anderson, reached out to me a few weeks ago. Malcolm grew up exploring the nearby forests and clearly feels protective of them. He lives less than a mile from the stands that are slated to be aggressively thinned. He is an arborist by trade and has a degree in botany from OSU. Many years ago, Malcolm was hired to create snags in the same stands that are now going to be logged – so he knows this forest. What concerns him is not so much the cutting of trees, but the size of the trees they’re planning to cut and the scale of the thinning (which will remove up to 65% of the conifers in some areas). He also reported that a substantial amount of new road has been constructed to facilitate the upcoming thinning. When he contacted city staff in search of answers, they weren’t very responsive.

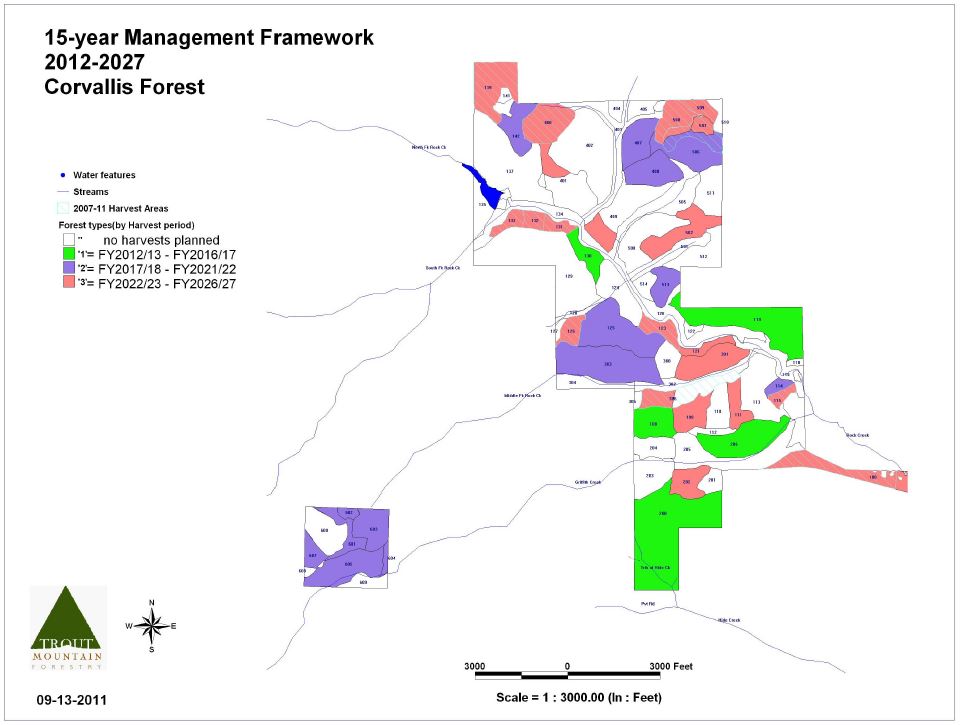

At this point, you may be wondering why the City of Corvallis allows logging and road construction in our watershed in the first place. The answer is a little complicated, but here are a few key facts. First, the city doesn’t just allow logging, it embraces it as their primary management tool in the watershed. They rely on the widescale and repetitive thinning approach provided by their forestry consultant. According to the city’s 15-year “Management Framework”, they’ve been cutting 900,000 board feet of timber (~225 log truck loads) each year. Second, it doesn’t have to be this way. There is no mandate to log the Corvallis Watershed and the revenue is not used to offset the cost of water treatment. In fact, ~20% of municipal watersheds in Oregon don’t allow any commercial logging. The Forest Service now manages its portion of the Corvallis Watershed largely as a reserve, with management activity restricted to recreating late-successional (old-growth) forest conditions. Corvallis could do the same. Third, the decision to log is a choice made by our city administrators and their forestry consultant, with tacit approval of our city council and the (now disbanded) advisory board. Finally, we now have decades of research connecting logging and road construction with adverse impacts to watersheds. These disturbances increase erosion, water temperatures, pollution, and peak flows. They also adversely impact the forest vegetation, wildlife, water and nutrient cycling, and carbon sequestration – while increasing wildfire risk.

The Corvallis Forest Stewardship Plan describes the history of logging in the watershed:

“Within the Corvallis Forest, approximately 1,000 acres were harvested during an 80-year period ending in the late 1980’s. Then, controversy over the effects of clear-cutting and the need to protect older forests for the northern spotted owl and other wildlife species put a stop to the harvesting program, which had been administered by the Forest Service. Several attempts to re-initiate timber management in the subsequent decades failed due to ongoing citizen concern about environmental impacts.”

After a ~20-year period of no logging, the pendulum began to swing back toward timber extraction around 2005. The change was prompted, in part, by the hiring of a forestry consulting company, Trout Mountain Forestry (TMF) to develop the stewardship plan and manage the Corvallis Forest. It should come as no surprise that a forestry consultant hired to develop a management plan would include active forest management (logging) as a key component. One wonders about the inherent conflicts of interest in that process. Several folks who were involved have described it as fraught with favoritism. The former mayor, public works director, Benton Co. Parks Director, and dean of the College of Forestry all reportedly supported the move to restart logging. Conservation-minded folks fought back, but were overruled and outnumbered. They were promised stewardship would be the primary goal of any logging.

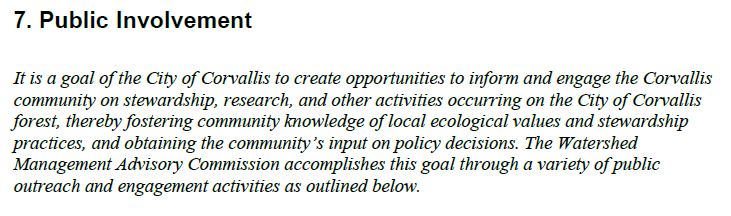

When I tried to learn about the thinning project Malcolm had told me about, I couldn’t find any reference to it on the city’s website. The only citizen oversight body, the Watershed Management Advisory Board (WMAB), is listed as “disbanded”. The last meeting was held in February of 2020, more than two years ago. The watershed is managed by Corvallis Public Works, but there’s no information about the project on their webpage, either. The city has a webpage for the Corvallis Forest, but it has no mention of the thinning to be found. Having searched the most logical places, I looked for a public notice in the Gazette Times – without success. Since the Corvallis Forest is publicly-owned, I figured surely there must have been some public notice of their logging plan (e.g. following Oregon’s Revised Statutes regarding public notice, ORS 193.020). While I cannot state with certainty that the city’s failure to provide any public notification of their thinning project was illegal, it clearly violated the stated commitments to public involvement in their own stewardship plan:

Since I couldn’t find any published information about the thinning project, and I’d heard it was supposed to begin soon, I headed up to the watershed to take a look. Anyone with a valid C2C Trail permit can legally travel through the watershed which starts about 3/4 of a mile past the gate at the end of Old Peak Rd. [Note: this section of the C2C Trail is now closed to the public until May 31st due to the logging project]. Soon after entering the watershed, I noticed the many trees marked with blue paint rings (indicating they will be cut). A few of the bigger trees marked for cutting are visible from the main road, but most are located further in the forest. One wonders if this was intentional so as to avoid complaints from the C2C Trail users. Like Malcolm, I was immediately struck by the size of the trees to be cut and the scale of the operation. It was hard to imagine how cutting so many healthy, old trees could fit with the city’s stewardship goals.

After my visit to the watershed, I was outraged and wanted some answers. The lack of public info., looming deadline and big trees marked for cutting were all deeply concerning. If this is “stewardship” of our community forest, it seems fundamentally inconsistent with public values and expectations.

I eventually managed to speak with the city’s watershed specialist, Jeff Hollenbeck, to express my concerns and ask questions. Mr. Hollenbeck was hired in 2019 to oversee the Corvallis watershed and the management activities conducted by the city’s forestry consultant (TMF). We spent nearly an hour on the phone and have exchanged a number of subsequent emails. He explained that the city and TMF have been planning this logging for approx. three years. When I asked Mr. Hollenbeck about the lack of public notice, he told me, “… the primary way in which folks would learn about it is to monitor the city website for the minutes of the advisory board meetings“. When I explained I’d been unable to find any information on the city’s website, despite extensive searching, he said he’d check on it and get back to me. A few days later, he sent me a link to the city’s website calendar from July of 2021. If one has the time and knowledge to search through each month of the calendar, one can eventually find meetings, click on the titles and discover hidden documents. The harvest plan for the upcoming thinning appears near the end of a lengthy meeting summary (I’ve provided the meeting agenda and the city’s harvest plan here). It is notably NOT to be found in any of the logical places (e.g. on the Corvallis Public Works or Corvallis Forest webpage). It seems disingenuous to claim this buried document meets their obligation for public notice and engagement.

When it came to the details of the thinning project, Mr. Hollenbeck insisted the primary goal was restoration of the stands and the adjacent 3-acre meadow. His understanding was that the thinning would focus on smaller, crowded, diseased, and dying trees. I explained that was absolutely NOT the case, that they had marked a substantial number of the relatively large, healthy trees. He replied:

“I would say that that’s not the way the prescription was described to me, no the idea is to favor the bigger, older ones…the marking scheme out there I can tell you is very confusing,…they have these areas that are centered around a large, vigorous tree where they want to…encourage the advanced regeneration and …favor the big, lone trees…I sure as heck hope that they are not taking out large, vigorous, older trees…”

Mr. Hollenbeck’s response reveals a deep disconnect between stewardship goals and TMF’s management of the Corvallis Forest. If he is truly unaware that so many of the larger trees are going to be cut, then he is grossly misinformed. Surely, he must have visited the site and seen the marking! Managing the city’s contractor is the core of his job. Though TMF does not get a percentage of the harvest proceeds, their hourly rate is paid for by logging revenue. Forest management (logging) generates revenue which pays for more forest management which promotes logging to generate more revenue in a self-serving loop. It’s important to remember that the forest was providing clean water long before “active management” became the mantra. Both city staff and TMF are quick to point to the many stewardship projects funded through logging (though a knowledgeable source told me independent grant money pays for many of them).

With the dissolution of the city’s advisory board more than two years ago, there’s no longer any citizen oversight of watershed operations. Mr. Hollenbeck explained that the disbanded group will be replaced with a Watershed Operations Committee sometime in the future (and will likely consist of the same folks who presumably approved this thinning project). The process and timing for choosing the members of that committee are unclear. Excuses about the pandemic are used to justify the lack of oversight, though one wonders why they couldn’t have used video meetings like the rest of us.

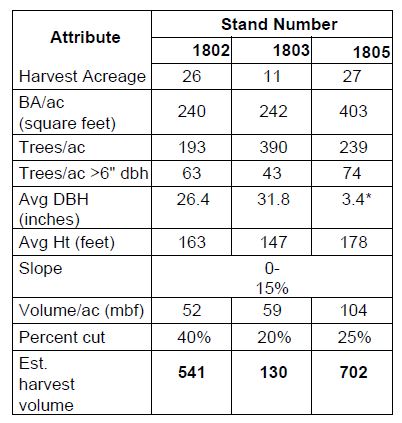

Once I got a hold of the harvest plan I began to review the written details and justifications for their logging. The first thing that stands out is the scale of the operation. The plan’s table (below) shows an estimated harvest volume of nearly 1.4 million board feet (mmbf) of timber from 64 acres of forest. That’s the equivalent of roughly 350 log truck loads – a lot of timber for this acreage. The second thing I noticed is that there are a lot of relatively large, old trees in these stands – as I saw in the forest. The advanced age is indicated by the substantial height and diameter (DBH) shown in the harvest plan. Keep in mind these measurements are averages for trees in the three stands they plan to thin (so many trees are larger). The average height ranges from 147 to 178 feet (the equivalent of a ~15-18 story building). In two of the stands, the average diameter of selected trees is more than 31″. For comparison, that’s significantly larger than the (28.4″) average DBH of trees cut at OSU’s controversial old-growth cut in 2019.

* Note: the Avg DBH for stand 1805 should read 31.4 (inches). The “Est. harvest volume” numbers are in thousand board feet (mbf).

The plan’s text says the trees vary from 60 to 100 years of age, but it also refers to “natural regeneration after homesteading and agricultural use ended around 1900“. This means the larger trees they will be cutting are likely 100-120 years old. For reference, this is 2-1/2 to 3 times the 40-year timber cycle used on commercial forest lands of the Northwest. One wonders how the city managers and TMF can justify cutting such big trees in the name of restoration.

The very choice of the term “harvest plan” displays an implicit bias toward timber production which many folks find offensive. After all, this is a complex, living ecosystem we’re talking about, not just a commodity for our profit and use. Keep in mind this is a “community forest” purchased and protected to supply drinking water (not timber). TMF’s harvest plan is full of the usual jargon employed by forestry consultants with an eye toward their ecologically-sensitive audience. It describes:

“Opportunities to increase structure and diversity and promote development of multi-age stand structure…foster resiliency and heterogeneity…regeneration and well developed native shrubs to contribute to structural variability…multi-aged, wind-firm stands with complex structure including vertical and horizontal heterogeneity…variable tree density with group selection openings to maintain young cohort and encourage understory development…Maintenance and recruitment of hardwoods…and ongoing recruitment of snag and lying dead wood features…”

Just reading the treatment prescriptions, it would be easy to think this plan is all about restoration. While the numbers reveal the left-brain, mechanistic approach of traditional forestry, the narrative seems designed to evoke positive emotions. They are not logging, they are “increasing, promoting, developing, encouraging and recruiting important features and functions of the forest.” The facade of ecological stewardship crumbles when one visits the forest and stands before the trees they plan to cut. At that point, it’s hard to ignore one’s right-brain sensitivities, which resonate with the natural world. Upon seeing the substantial number of large, healthy trees they intend to destroy, outrage is a natural response. The foresters write about increasing diversity, yet there’s already a surprising amount to be found – as one would expect in a century-old forest. And how exactly does cutting older, healthy trees and removing thousands of tons of biomass from the ecosystem support, “…the ongoing recruitment of snags and lying dead wood features“? If the plan were really about restoration, they’d leave all the logs in the forest to feed the soil. But that wouldn’t pay for their active forest management!

If you don’t find my arguments convincing, consider the critique of a prominent OSU expert who has worked in these forests for decades:

“As far as the harvest plan, I see no reason at all why they are doing this thinning. They just thinned the site in 2007 and 2009. Why does it need further thinning? It makes no sense to me. Also taking out 65% of the trees is not a thinning…..it is more like a “shelterwood”. What is the purpose of this? There is no need to log to that extent to “create future older-aged forests” (if that is their intent). Also understory development is horrible for MAMU [murrelets]. Shrubs like elderberry, salmonberry and other fruit producing plants attract predators (ravens and jays). This needs to be kept at a minimum to avoid increasing predation of murrelet nests. And here the goal is to “increase understory development”. Why? This is not needed to create older forest conditions in the future. No species are listed that need understory……there is tons of it already out on the landscape. Again their logging plan makes no sense.” (emphasis added)

Dozens of significantly older and larger (5 to 7′ diameter) trees already provide the multi-age, structural diversity TMF claims they will be fostering. These older trees with large branches (called “platform trees” for their nesting potential) are prime habitat for endangered marbled murrelets. Unfortunately, the watershed’s murrelet surveys were conducted during poor ocean-feeding years. While murrelets were detected only a mile from these stands, it is unlikely they were nesting in the watershed at that time. The absence of detections probably just reflects the poor ocean conditions during the 2018-2019 survey period, according to one of OSU’s murrelet experts, Kim Nelson. While it appears the city and TMF met the minimum legal requirements for murrelet surveying, conducting a large logging operation during the peak nesting season in prime habitat will inevitably impact many other birds.

In my discussions with both the city’s watershed specialist and the TMF forester, I specifically asked whether they had considered the enormous amount of carbon that would be released by cutting these older trees. A number of studies, including those by OSU’s renowned forest carbon experts, have concluded that the timber and wood products industry is the single largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Oregon (accounting for ~35% of our total). At the same time, Oregon’s forests sequester roughly 70% of our annual carbon emissions. I noted that the word “carbon” does not appear once in the 62-page stewardship plan for the Corvallis Forest (which was updated in 2013). Given the urgent focus on mitigating climate change, that seems like a colossal oversight.

It was telling to me that both gentlemen replied to the carbon question by mentioning the difficulty of calculating “additionality” – a technical consideration in determining carbon credits. I tried to explain that whether or not they could monetize forest carbon was not the point. By cutting these older trees, they will destroy natural carbon reserves that have developed over a century. I predicted citizens will share my outrage when they learn what’s going on. It seems the inability of foresters to prioritize carbon reserves is a common malady. They have a hard time valuing parts of the forest they can’t monetize, measure or cut. Mr. Hollenbeck assured me that the next revision of their stewardship plan would likely include carbon considerations. However, one doesn’t need a revised plan to understand that cutting these older trees is the wrong thing for our warming world – and this community forest!

*****************************************************************************

If you’re concerned about the management of the Corvallis Forest and Watershed, here are some ways you can help to create positive change:

- Show your support for the new grassroots stewardship group, Friends of the Watershed by visiting www.friendsofthewatershed.org and signing the petition to stop the logging.

- Send an email message to the Corvallis Mayor and City Council to demand change: mayorandcouncil@corvallisoregon.gov

Request that they encourage Corvallis Public Works managers to make the following changes:

-

- Provide public notice and opportunities for a thorough public review of all logging projects as promised in the Corvallis Forest Stewardship Plan (CFSP)

- Appoint a truly independent citizen advisory board (focused on stewardship), not an operational committee (focused on active management of the forest)

- Revise the Corvallis Forest Stewardship Plan to prioritize carbon sequestration, wildlife habitat, and forest stewardship – NOT logging!

- Stop all road-building in the forest. Roads have significant adverse impacts, increase fire risk, and promote logging.

- Stop logging under the guise of stewardship and restoration in the forest!

3. Submit a “Letter to the Editor” at a local newspaper (Gazette Times or Corvallis Advocate).

Please take a moment to create positive change in the management of this amazing natural resource that belongs to Corvallis citizens. Let our city leaders know we expect and deserve better management of our community forest. Together, we can change the future of the watershed and the Corvallis Forest for the better!

Thanks for your continued interest and support!

Doug (and Friends of OSU Old Growth – www.friendsofosuoldgrowth.org)